News Flash

by Tausiful Islam

Dhaka, July 4, 2025 (BSS) – A statement by then-autocratic Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina regarding the students’ logical demand for quota reform in government jobs added a new dimension to the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement.

Thousands of students, defying obstruction by leaders and activists of the banned terrorist outfit Chhatra League, took to the streets at the base of Dhaka University’s Anti-Terrorism Raju Memorial Sculpture. The next day, Hasina’s loyal brute force, the Chhatra League, launched an attack with local weapons on the students' protest, leaving over a hundred students injured. Mohiuddin Roni was among those students. Due to an injury to his leg, he had difficulty walking, but he moved around Dhaka city in an ambulance during the movement.

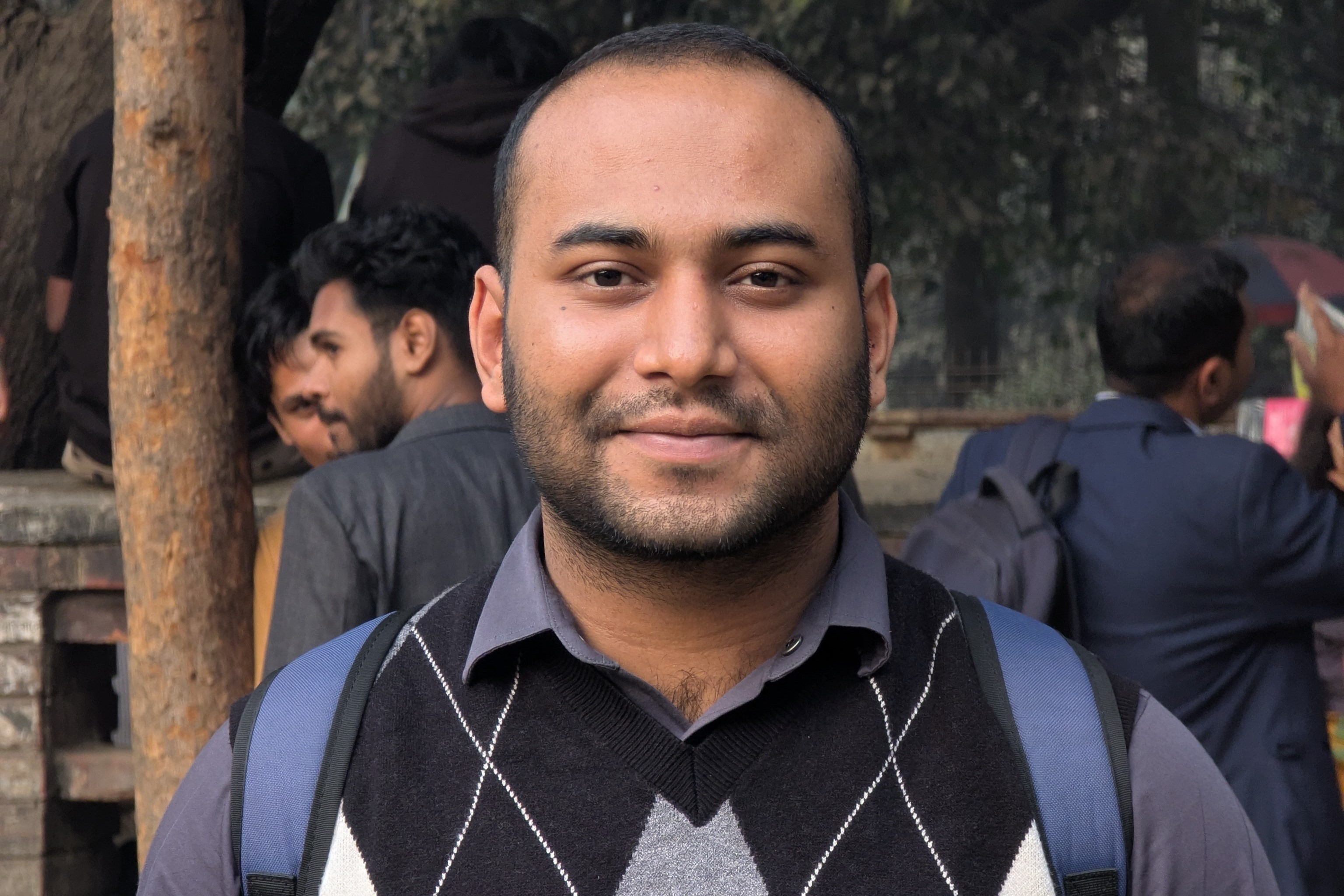

Roni, son of Md. SelimHowlader and Renu Begum, hailing from BarishalSadar Upazila, mobilised student masses across various parts of the capital during the July uprising. Speaking to Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS), he recently reflected on the course of the movement and shared his memories.

BSS: It’s been almost a year since the July 2024 mass uprising. You were on the frontlines of that movement. Every moment of July is memorable, but among them, which particular incident do you remember the most?

Mohiuddin Roni: The mass uprising of July 2024 is an inseparable part of our lives. Even if we wanted to, we couldn’t erase that memory from our minds. I can remember the entire time because it shocked our minds so deeply. I’m still traumatised. Even now, I often wake up suddenly from sleep at night. I still have dreams related to July Uprising. These events are simply unforgettable.

After the uprising, I became severely traumatised. The doctor advised me not to get stressed and to try to remember the memories less. But still, these things can’t be set aside—they come to my mind constantly.

What I remember the most is the beginning. The plot of the uprising started on July 15 when the (banned) Chhatra League launched a sudden attack on the students of Dhaka University. The students were bloodied in such a way—it’s impossible to forget. I was injured that day too. They were beating everyone indiscriminately. I saw it all happen right in front of my eyes. That day I was dumbfounded. My mind couldn’t function—what just happened? What did I witness?

The women students of Dhaka University were attacked by their own brothers, friends, classmates—those who were in the Chhatra League. It’s disgusting to even think of them as friends. But many of our friends were involved with the Chhatra League. Once, we used to hang out with them, sit together, go to classes together. That these people could become so brutal, could act like hyenas—I just couldn’t accept it.

That day it became clear in my mind—this can’t go on any longer. This needed the highest form of punishment. Hasina needed the highest form of punishment. That day, the plot was written. And the final plot took shape the next day. That day, Chhatra League men were dragged out from every hall. Students took control of the halls. That very day, students drafted the final blueprint of the uprising.

BSS: Are you really that surprised by this attack from Chhatra League? Because even before this, Chhatra League attacked students during the ‘Safe Roads Movement’ in 2018. Later, they also attacked during the quota reform movement and the anti-Modi protests. There were even allegations of attacks on female students.

Mohiuddin Roni: I wasn’t surprised then. When Chhatra League attacked during the 2018 quota reform movement, I saw it happen right in front of my eyes. I also witnessed the Safe Roads Movement. I’ve seen other attacks too, and I’ve seen incidents of murder and rape all over the country. Watching all of this, a kind of resistance—a kind of mental preparation—had already formed. I used to think, maybe this is the system.

But the July 2024 movement had a different dimension, because that movement was completely logical. A resolved issue from 2018 was dragged back in with blatant deception towards the students. The government could’ve solved this very easily, could’ve removed the discrimination in a peaceful way.

I’ve seen Chhatra League’s attacks in 2018 too, but the way this one movement was suppressed so brutally—that was unprecedented. There had been attacks before, but never in such numbers, never so ruthlessly. We were ordinary students. We didn’t even have sticks in our hands. This wasn’t a movement of students from a single institution—this was a movement of students from across the country.

On July 15, not just one or two—we were almost all injured in some way. More than a hundred students were injured. But we were so helpless that we couldn’t even build resistance that day.

When Chhatra League saw that their own cadres from Dhaka University weren’t enough, they started hiring thugs and listed criminals from outside. They brought in hired men from different places to attack students. At that time, it felt like none of them were students. The whole thing was terrifying.

That very day, the thought came—maybe this is the beginning of the final downfall. From now on, there won’t be movements—there will be a mass uprising. Those of us who were on the ground then made a decision—if we endure this, we’ll die in jail. But if we stand up, victory will come.

Uprooting the root of discrimination became urgent at that point.

BSS: The quota reform movement progressed in several phases. At which stage of the movement were you most active?

Mohiuddin Roni: From the day the High Court ruled to reinstate the quota, I became active on social media. However, after that, I went home for Eid. The movement really gained momentum after I returned. From the beginning of July, I directly engaged in the field.

BSS: The movement took on a different dimension in July. Blockades were put up repeatedly at Shahbagh intersection. Did people support the movement at that time?

Mohiuddin Roni: First of all, the demand was completely logical. People across the country saw how the nation was being mocked. Everyone living in Dhaka was aware of the movement. They knew a fascist government was continuously deceiving the nation. People were frustrated with that government.

When they saw students were taking to the streets with reasonable demands, their parents also joined the streets alongside the students. The public became part of our movement.

The public understood that the government was cheating them. And it was urgent to raise a voice against that cheating.

At the blockades in Shahbagh, it wasn’t only students—ordinary people also joined.

BSS: At that time, law enforcement agencies were arresting people en masse. Many were martyred by their bullets. Were you afraid?

Mohiuddin Roni: Since the railway reform movement, I had experience. I had a clear idea—what the police could do, and their capacity. Our hero Abu Sayeed had stretched his arms to embrace martyrdom. But I did not want any of my brothers or sisters to be shot and die, because Hasina’s mercenary forces had no mercy or compassion. They came only to kill.

So, I felt there was no benefit in taking a bullet. If I took a bullet, then another 10 would too. At the end of the day, 10 mothers would lose their children. From this thought, I felt my first responsibility was to keep my friends, seniors, and juniors safe. If we all survived, then it would be possible to continue the movement.

We had no weapons—we were unarmed. Our strength was our friends, classmates, students, and the people. But if we destroyed our own resources, we would gain nothing—only the enemy would benefit.

So we went, organized, to different places inside and outside Dhaka, advising those monitoring the movement—so that it could continue while avoiding damage.

The most crucial part was—after being injured on the 15th, I couldn’t even walk properly. I had a severe injury on my foot. I couldn’t run—running caused extreme pain. I had to move by ambulance. That was some relief.

After being injured on July 15, I first took shelter at the Dhaka University Medical Centre. Even there, I was the main target of Chhatra League. They probably thought I was mobilizing the movement. They came searching for me at the Medical Centre. The staff already knew me—I had once protested there over medical reforms, so I had a good relationship with them. Mahin Sarkar was also there then; he was injured too. I couldn’t even think about checking on him.

Wherever Chhatra League went, they beat whoever they found. Then the staff took me to a doctor’s room and hid me under a table. They locked the door from outside. Later, they took me out and put me in an ambulance. But ambulances were being checked at that time. I was laid on the floor of the ambulance. Female students of the university protected me, covering me with their bags so no one would know I was there.

From there, I was shifted to Dhaka Medical College Hospital. Some injured Chhatra League members were also receiving treatment there. I didn’t know them—thought maybe they had come with some of us. Later, listening to their conversation, I realized they recognized me. They said among themselves, “This is Roni.” Then they called more people by phone to come beat me.

Some staff at the hospital recognized me from previous protests. Chhatra League was trying various ways to enter the hospital to beat me. Then some outsourcing workers put me into a large carton and took me to their secret warehouse. They told me, “Brother, don’t move. They’re searching. If they find you, they’ll kill you.”

At some point, I heard Chhatra League was entering the hospital and beating injured students too. I kept in touch by phone, trying to contact friends. At night, when Chhatra League calmed down a bit, I told the younger students where I was. They came but couldn’t find me at first. Then Sujon came and took me out through the back way. I left by CNG to Akib’s house.

Akib’s parents are advocates. I thought—if police or intelligence came looking, at least they could respond legally. I still couldn’t walk. I took initial treatment there. From the next day, I again participated in the movement.

BSS: The government had imposed a long curfew. The internet was blacked out. Many frontline coordinators of the movement were picked up by law enforcers. Where were you at that time? How did you continue your involvement in the movement?

Mohiuddin Roni: We were aware from the very beginning. I kept telling everyone—not to fall into the trap of the law enforcement agencies. Suppose they really killed Nahid Bhai—where would we have found him? So, I kept telling everyone—not to get caught in any way. Unfortunately, in the end, they caught a few of them.

I myself couldn’t walk then, but still rented ambulances to get around. I went to various places by ambulance. Even if other vehicles were checked, ambulances usually weren’t. They would see and let us go. I stayed at the houses of younger brothers on campus—one after another each day. Many times I stayed at the hospital too—parking the ambulance there and spending the night inside it.

BSS: Were you in Dhaka the whole time?

Mohiuddin Roni: No, I wasn’t only in Dhaka. I also went to Madaripur. I went to a few neighboring districts too—all by ambulance. Because Nahid Bhai and others were inside—during their absence, we had to carry the movement forward by any means.

Rifat Rashid and others were outside then. They set the movement’s policies and communicated them to various groups. We circulated those and tried to send them out by different means as much as possible, so they could reach the general public.

During the internet blackout, we also tried to stay connected with expatriates. The expatriates spread our messages in many places. They were active on Facebook. Pinaki Bhattacharya, Elias Bhai, Konok Bhai—they ran excellent activism. They connected and organised the expatriates.

We told them—if possible, let everyone in their areas and homes know, announce on the local mosque’s microphone so people know what’s happening where.

And they really did that.

BSS: You were not part of the Anti-Discrimination Student Movement committee. Is there any particular reason for that?

Mohiuddin Roni: I felt that even if I wasn’t on the committee, standing by their side might give them even more strength. There is a position outside the committee—which often turns out to be more effective.

BSS: You didn’t join any political party even after August 5.

Mohiuddin Roni: For a long time, I have been working with various volunteer organizations. I more or less understand—how leaders are made. If none of us step down or promote one another, everything becomes centralized—everywhere it’s just “me.”

That’s why I have always tried not to be center-focused. I want people to understand—I am with the masses, not trying to make myself a leader.

I have never wished to become a ‘cult figure’ around anyone because we have always seen—Mujib, Zia—they were politically turned into cult figures.

Nowadays, when someone gets involved in activism, gradually they want to taste power.

That’s why I have never thought about joining politics. I never thought I would go to power. If I’m not in a position, someone new can come into that position, a new leader will emerge. I didn’t want my presence to become a barrier to someone else’s growth.

BSS: During the movement, a video went viral showing you chanting slogans. At one point, when the police tried to arrest you, lawyer Manzur Al Matin came forward in your defense. When and where did this happen?

Mohiuddin Roni: During the movement, I became acquainted with some personnel of law enforcement agencies. They occasionally gave me information — what was happening, what wasn’t, or any warnings about potential dangers.

At that time, the police had one clear order: to arrest me at any cost. There was a direct warning like that. MuktiJuddho Mancha had filed a case; in which I was the prime accused. Because of this case, the police were actively searching for me. If they caught me, they would take me away — that was the situation. They might not kill me, but would cripple me. If they arrested me, they would also arrest others, and eventually the whole movement would be stifled. So, it was always on my mind that someone had to keep the movement going and inform the public about our next steps. I even relocated my parents to different places, never letting them stay more than a day or two in one place — so that they couldn’t be found or blackmailed through abduction.

Now, the incident you are referring to happened on July 31, during the “March for Justice.” We were chanting slogans in front of the High Court. We were determined to break the police barricades no matter what. At that time, Shahbagh police station’s OC came and threatened to arrest me no matter what.

The police fired tear shells and rubber bullets, clearing the whole area. There were a few boys including me; the rest were girls. Our younger sisters were trapped. If I had left them and run away, I would have lost their respect. I thought, even if I die, I can’t leave them behind. Then more people started gathering around us. We began chanting slogans again. Suddenly the police advanced to arrest me.

That’s when Manzur Al Matin arrived. He asked why they wanted to arrest me. In fact, every time the police tried to arrest us, lawyers saved us.

At one point, the OC tried to grab me by touching one of the girls. I retaliated and pushed them back. The police got confused and lost their nerve. Many of them actually didn’t want to beat the students. They were forced by their jobs but didn’t want to from their hearts. They were even telling each other, “Don’t touch them.” The OC himself got scared.

Later, more lawyers came to support us, and our strength grew significantly.

BSS: Hundreds of people were martyred during July. The aspiration for an egalitarian and impartial state expressed through July—will that achievement be lasting?

Mohiuddin Roni: Generally, we call it the July Mass Uprising, but I always say July was a revolution. A revolution is a process, and a mass uprising is a part of it. What happened was an uprising — a mass uprising — but the revolution is still alive in people’s hearts. The seeds of that revolution lie within those who participated.

Now, an interim government has formed through the uprising. Three student representatives were part of it, now two of them are in the government.

After Dr. Muhammad Yunus came in, there was a renewed sense of hope among us. Because a country has many organs that require thousands of people to run. The government struggles with a small team, which is understandable. I remain hopeful they can manage. There’s still time. With the people’s involvement, great things are possible.

We must remember, even if Sheikh Hasina is gone, her proteges remain. The system she created — all still exist.

This uprising will turn into a revolution and change the country only when those of us who hold July in our hearts study hard and turn to libraries. We must vow to develop ourselves over the next four or five years in a way that we can enter the system and change it from within. Maybe after ten years, the seeds sown in July will bear fruit. This isn’t an instant change. It won’t happen overnight. This is not a movie.

Waiting on an interim government won’t suffice. If 180 million people have even two problems each day, can Yunus solve 360 million problems alone? No. We must solve our own problems. We must own our country.

Now the sole task of the interim government is to build a feeling among the people that we are all Bangladesh. Unless we change ourselves, July will be lost in words, neglect, and mockery. But we do not want to lose July. We won’t let July fade away, InSha Allah.